After Chess and Go, Castle of Mind opens a new dimension in logic-strategic games

Opinion of Zombor Kovács

One of the coolest gifts in my childhood was Zdzislaw Novak’s book, 50 board games, which my uncle who worked as a mason saved me from the attic of a to-be-demolished house. It is obvious that he thought of me then, since not that long before that, I bothered him with playing chess with me when my parents were gone for a few hours in the morning.

One of the coolest gifts in my childhood was Zdzislaw Novak’s book, 50 board games, which my uncle who worked as a mason saved me from the attic of a to-be-demolished house. It is obvious that he thought of me then, since not that long before that, I bothered him with playing chess with me when my parents were gone for a few hours in the morning.

The title of the book is honest, it tells you all about the content, it really has a description of 50 board games, along with the necessary boards and game discs. It was a perfect gift. It took me a summer to try all of them – or almost all, because the last twenty pages had a description of the Go game. It seemed so complicated for a ten year old that if I could only describe a game with so many letters then I wouldn’t even start collecting the black and white pawns from tiny objects around the house to be able to play the game. Because by the time the book got to me, the pawns had been lost, so I had better put it on the colored boards, which I could find around.

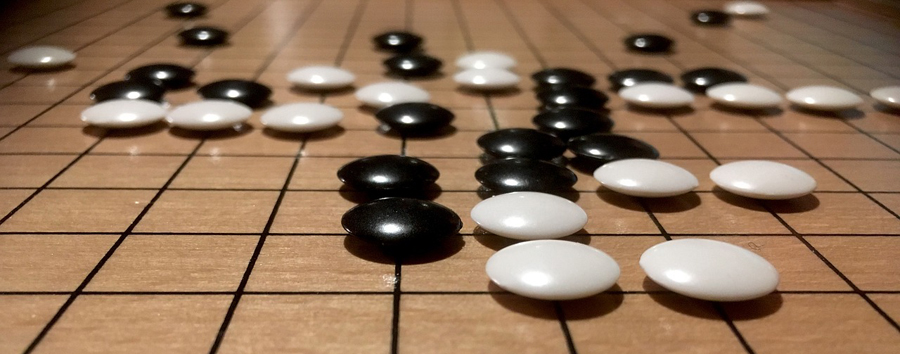

So I finally got to try Go as a college student, and sometimes I happened to party with some pretty strong Go players around the University and I was fortunate enough to be defeated. In the first few games, it became apparent how much more complex Go is than chess and anything else, though its rules are much simpler.

I could only formulate the reason after quite a few games why exactly was it more complex. In chess (as I have seen it, at least) the moves bring about a change in the immediate vicinity of the stepping figure and indirectly affect the board as a whole – the new situation resulting from each step can be viewed from the perspective of the figure moving. Whatever happens on the board, it can be viewed and understood, it can be gauged when we begin to move the figure performing the step and follow it step by step to see how it ripples everywhere. There are steps that do not directly affect much of the board: like throwing a stone into the pond and if it is not large enough, the ripples of the stone won’t reach the distant parts of the pond.

My knowledge meant nothing in Go, because it was much more complex to assess the consequences of a move. In Go, the stones once placed somewhere will not move until they are removed or the match is over. Due to the game mechanic of surrounding areas, seeing the effect on the whole board of a placed stone is often not trivial. And many times there are no such hints for getting started like in chess. I often had the feeling while playing with more experienced players that I had no idea how the placement of a stone affected the whole situation. This was true especially at the middle of the game, when groups of stones that had already been placed on the board started to come together and every mistake I made in the opening rushed towards me at once. In Go, every game I lost confronted me with the fact that I couldn’t see the board as a whole.

Of course, due to the lack of time, we often didn’t start the game on the complete 19 × 19 board: the complexity of the game and the lack of grasping the whole playing field came out much less on a 13 × 13 or smaller board. On the complete board it took me around 40-50 minutes before my position collapsed, which I explained to myself that yes, this 361 grid point board is big and whatever, on smaller boards I still manage quite well.

Then I started playing a new game called Castle of Mind (COM). A new element in the game is that the hit does not take place where the piece actually moves, instead, one of the enemy pieces of the same color can be taken down across the board. And this (seemingly) very simple element has revolutionized my view about board games. The mechanics of the game are such that from the very first moment, every move directly affects the entire area of the board, so already in the third step, I was tormented as on the complete Go board after half an hour. You have to see and see through the whole board for success, and that helps you get to what we call spatial thinking… the effects of our moves from the most unexpected places and situations appear and pull through my calculations and my approach of the classic “I muster through all the effects one by one” reaches an unimaginable complexity. Something else has to grow in my mind, new neural pathways, new connections.

Then I started playing a new game called Castle of Mind (COM). A new element in the game is that the hit does not take place where the piece actually moves, instead, one of the enemy pieces of the same color can be taken down across the board. And this (seemingly) very simple element has revolutionized my view about board games. The mechanics of the game are such that from the very first moment, every move directly affects the entire area of the board, so already in the third step, I was tormented as on the complete Go board after half an hour. You have to see and see through the whole board for success, and that helps you get to what we call spatial thinking… the effects of our moves from the most unexpected places and situations appear and pull through my calculations and my approach of the classic “I muster through all the effects one by one” reaches an unimaginable complexity. Something else has to grow in my mind, new neural pathways, new connections.

I hate and love this game at the same time because it makes my brain smoke from the first step like no other game – it’s like at workouts, doing a push-up, which shows exactly where the flaws in the body are. The game shows exactly when I narrowed down to one side of the board and ignored the rest, strayed and stepped back – a loss of tempo, playing with a strong opponent, has the effect until the end. And maybe that is the difficulty of really improving spatial vision and thinking… by relentlessly confronting narrow-mindedness, which hasn’t been a problem in any other board games so far.

So let’s play!